2022 was a tough year for everyone living in Australia. From floods to fires to storms to public health crises, disasters have hit across the country at a rate that shows no signs of slowing down any time soon. As a widely multicultural, yet primarily English-speaking country, Australia’s many recent disasters have revealed one major crack in our emergency response systems: it is catered to English-speaking individuals.

A good number of Australians don’t speak English at home, making preparation and response to disasters much harder for them. While community groups often do life-saving work in these situations, they are typically lacking in funding, poorly equipped, and not properly trained to handle disasters. So what can be done in terms of crisis management? And what should authorities put their focus towards for best results? Let’s discuss.

Recognising and Addressing Language Barriers

Around 23% of Australians surveyed in the 2021 census speak a primary language other than English in their homes. Most have some capacity for English (reading, writing, speaking, or listening), but fluency isn’t always common in their communities. For these people, navigating an English-speaking world is difficult enough during their normal day-to-day life — imagine what it could be like during a catastrophic flood or damaging hailstorm.

Adapting the Messaging

Public transport is one clear example. Many non-English speakers navigate public transport by memorising signs, symbols, or landmarks, rather than reading maps or listening to announcements. For this reason, many high-traffic public transport hubs in Australia, like central bus or train stations, have upgraded to digital signage that cycles through languages as a way to keep all passengers informed. This is a fantastic development in community awareness over the last few years, and we applaud it. During a crisis situation, however, these communications can be left by the wayside — potentially endangering lives. Many transport authorities (indeed, authorities of any kind) are likely to release English-only emergency communications that won’t register to those who aren’t fluent.

A Slow Read During Urgent Times

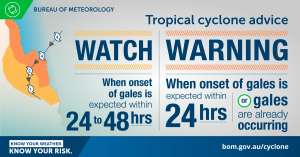

Imagine trying to understand this cyclone advice graphic if it was in a language you didn’t read fluently:

That’s a complex image for fluent English speakers, let alone English-as-a-second-language speakers. Between uncommon words like “onset”, “gales”, and “occurring”, and the non-linear formatting, it takes effort to decipher the exact meaning — effort that, in the middle of a disaster, cannot be afforded.

This is what most non-English speakers have to face during disasters, and it can be extremely stressful trying to organise your own translation from the community or family members, in order to know what to do. One of the first steps that authorities who publish disaster warnings can take to help non-English readers is to use the simplest, clearest English and formatting possible. This drastically reduces translation times and also any stress placed on non-English-speaking locals.

Disaster Preparedness

To mitigate the effects of emergency situations before they happen, non-English speakers and their community groups can encourage local councils to include them in disaster preparations. Forecasts predict that the current pace of weather and health crises will not slow down, so getting ahead of things can make a world of difference. Both local and federal government websites across Australia offer natural disaster preparedness guides and some local councils already understand the need for translation. For instance, we worked with local councils in Queensland to translate their Disaster Management leaflets in a wide range of languages, including preparing multilingual voice-overs for radio ads and website voice alerts. However, many councils still have no solution for acute life-threatening disaster response for their culturally and linguistically diverse communities. Translation software might be available on the users’ end (think Google Translate), but it relies on infrastructure like an internet connection that may not be available in the midst of a natural disaster. If possible, community groups should advocate for their governments to engage language professionals for their urgent disaster response communications and plans and let their community know where to access them.

Leveraging the Media

Speaking of plans, one action that governments can take to help prevent unnecessary harm during disasters is to work alongside the media outlets that already service the minority communities in their area. Whether that’s a small TV or radio station (Radio 4EB, in Brisbane, is an example) a newspaper, a text message alert service, a WhatsApp group, or a social media channel, every community has its ways of using media to keep up-to-date with current events. The people working with these media often already have a great deal of experience taking English information and distributing it to their non-English-speaking community. Minority-run media channels are a great resource for governments and disaster response organisations to utilise when preparing for catastrophic events. They have a lot of expertise to offer outside of disaster scenarios too.

With the summer forecasted to be hot and dry and with bushfires, flash floods, and powerful storms all on the docket, Australian authorities can learn from the past year’s disasters and make sure language services are available to all. Translators, both human and digital, are great resources in general, and more so in moments of crisis, but can’t be everywhere at once. Crisis Management is about being proactive and prepared. That’s why preparedness is the number one goal for disaster response, and translation, as well as other language services like voice-over, should be central to that goal in order to protect everyone during times of crisis — no matter which language they speak.